By Clifford K. Shipton

Director, American Antiquarian Society

Founders' Day Address

February 27th, 1964

It was with great pleasure that I received President Mackay’s invitation to speak to you today. As keeper of the archives of Harvard University, and of the records of her sons, I have long been aware that they had an influence in the founding of the University of New Brunswick. As the representative of my university, I cannot but feel that I am visiting a daughter in whom we take pride. If, indeed, the University of New Brunswick is a daughter of Harvard, she is the sister of the American Antiquarian Society, of which I am the Director, because of the part Dr. William Paine played in the founding of these two institutions. The last of his male descendants was a close friend of mine, and the great brass andirons from the last of the Paine houses were given to me, and in my fireplace they serve as a constant reminder of the long road back to the founding of this Province and University.

If any living man can speak for Dr. William Paine, it is I, and I would like to take this opportunity both to speak for him, and to share with you my acquaintance with him. The town of Worcester, Massachusetts, in which he was born in the year 1750, had been resettled after the removal of the Indian menace only thirty-five years before, but it had little in common with the rough frontier towns of later generations. It consisted of a compact group of solid, handsome frame houses, and it had mills, a school, and a church; for the sons of the Puritans refused to adjust their lives to the wilderness, but carried a full-flowered civilization with them as they advanced westward.

If any living man can speak for Dr. William Paine, it is I, and I would like to take this opportunity both to speak for him, and to share with you my acquaintance with him. The town of Worcester, Massachusetts, in which he was born in the year 1750, had been resettled after the removal of the Indian menace only thirty-five years before, but it had little in common with the rough frontier towns of later generations. It consisted of a compact group of solid, handsome frame houses, and it had mills, a school, and a church; for the sons of the Puritans refused to adjust their lives to the wilderness, but carried a full-flowered civilization with them as they advanced westward.

William Paine’s father, Timothy, had graduated at Harvard and would have practiced law, but for the New England insistence that an educated man who could live on the income of his lands and investments must devote most of his time to public service by filling unpaid or ill-paid offices. Timothy was elected to all of the town offices, one after the other, and in time became Justice of the Peace, Register of Probate, Register of Deeds, guardian of the local Indians, Representative to the legislature, and finally a member of the Governor’s Council.

Young “Billy Paine’s” schoolmaster was John Adams, later second President of the United States, who described him as “a very civil, agreeable and sensible young gentleman.” At college, Billy was placed second in a class of more than forty, according to the New England system of ranking students by what was called “dignity of family,” which did not mean wealth or a distinguished name, but was a measure of the father’s service to the commonwealth by his acceptance of election to civil office. This may not seem to us to be democratic procedure, but it was democracy to a degree which made it impossibly for Dr. William Paine, Loyalist though he was to be, to be comfortable in the social and political conditions then prevailing in England. In that land, although the rights of the individual were better protected than in any other civilized society which had ever existed, government was in the hands of an oligarchy, and except for a few boroughs, office was achieved by influence, and was regarded as a sinecure rather than as a social duty.

The spectacular democratic reforms of the Puritan Commonwealth had failed because the common man did not have the education necessary to make them work, and the Restoration of 1660 had so turned back the clock that the lost ground was not to be fully regained until 1912. But the Puritan concept of democracy in government had continued to flourish in New England, where every male inhabitant had a voice in public affairs at the town level, and, in practice if not in theory, exercised the franchise at the province level. This was the society of which the Paine family was a part, and although they might sometimes think that the public voice was wrong, they could not be at ease in a less democratic society.

Billy Paine graduated from college in 1768 and immediately went to Salem to study medicine as an apprentice to Dr. Edward Augustus Holyoke, who was probably the best of the New England physicians who had not studied in Europe. In Salem, Paine moved in the highest social circles, dined with the Judges, friends of his father, and in 1773 married Lois Orne, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. There was a family tradition that he went to England about this time, and his notes on the lectures of the famous Dr. William Hunter of London may date from this period. At all events, Dr. James Latham, Surgeon to the Suttonian method of inoculation against smallpox. It was fifty years since Cotton Mather, the eminent Puritan clergyman, had in spite of the fierce opposition of the public and of the most prominent physicians, convinced the town of Boston that it should permit inoculation. The town of Salem, in spite of the efforts of Dr. Holyoke, as still not ready for this reform of medical practice, and it formally voted not to “allow Doctor William Paine to Erect a Hospital of Innoculation.”

This rebuff no doubt had some effect in causing the Doctor to return to Worcester, where in July, 1773, he had invested ₤200 in a partnership with another physician and an apothecary to open the first drug store in the town. In Salem he had followed the lead of Dr. Holyoke, who had no use at all for the local Whig politicians, but avoided any participation in political matters, and throughout the evil days to come was to keep his mouth shut and to devote himself strictly to his practice, which he regarded as his prime duty. In Worcester, Dr. Paine could not avoid taking a stand. The Whigs had turned Judge Timothy Paine out of the Council in 1769, not so much because of his political views as to annoy the Governor. In August, 1774, the Judge accepted appointment to the Mandamus Council, an affront which could not be accepted by a people accustomed for almost a century and a half to the popular election of the members of both houses of the legislature. In town meeting, the two Paines courageously opposed the Whig majority, and in the end were described by vote of the town as being two of its five obdurate Tories.

What made a Whig or a Tory in the New England of 1774? I have written the biographies of many of both, and have found no two individuals with precisely the same motivation. Speaking solely for New England, for the other colonies had other causes which finally merged with the revolution, there are certain general principles. The growth of population, trade, and settlement made it essential that the ties which bound the parts of the British Empire be strengthened. That strengthening, the new colonial policy, was eminently fair, eminently reasonable, and eminently considerate of the interests of the colonies. But the four New England provinces had for five or six generations been practically self-governing states, and they were disinclined to yield any of their independence in order to further the interests of the Empire. The English Whigs harked back to Cromwellian times and pointed out to their American friends and parallel between the political situation of 1774 and that of 1645. The New Englanders accepted the idea but pointed out that the parties had changed, that they were now fighting for the King and liberty against the Parliamentary army and tyranny. But such comparisons were confusing, for the admirals of the British navy, who in general sympathized with the Whigs who had controlled Parliament, sat out the struggle and called it “the King’s War.”

In New England, lawyers and civil officials like Judge Paine so generally boycotted the Whig movement that the revolutionary governments were hard-pressed to find men to fill judicial offices. Physicians like Dr. Paine tended to be Loyalists because they were more interested in their practice than in politics. In Worcester County, several of the Congregational ministers also were Loyalists. Indeed one sometimes hears that a half or two-thirds of the then living graduates of Harvard College were Loyalists. Take it from the mouth of this old horse, however, that the accurate figure is sixteen per cent. It would be more to the credit of a Harvard education if that figure were higher, for right and wrong were more evenly divided than that.

For some years the Paines had had the reputation of being Loyalists. Once when the Bench and Bar were dining at the Paine mansion, the host proposed a toast to the King. Some of the guests were about to refuse when young John Adams whispered to them to comply, saying that he would return the compliment. When his turn came, he gave as his toast “the Devil.” Judge Paine started up in a rage, but his wife turned to him and said loudly, “My dear! As a gentleman has been so kind as to drink to our King, let us in our turn, by no means refuse to drink to his.”

When Judge Paine accepted the King’s appointment to the Mandamus Council, the time for joking had passed.

Immediately there began gathering around Worcester ominous clouds of armed men. For some of those who were closing in to make an example of Paine the tension became unbearable, but he calmly awaited the blow. His report to Gage of the events of August 27 is one of the most moderate:

The People began to assemble so early as Seven oClock in the morning, and by Nine … more than Two Thousand men were paraded on our Common. They were led into town by particular persons chosen for that purpose, many were Officers of the Militia, and marched in at the head of their companies. Being so assembled they chose a … Committee to wait upon me … I received them first at my Chamber Window, but upon assurance from them they had no design to treat me ill, I admitted them into my house. They then informed me … they were … chosen … to wait upon me to resign my Seat at the Council Board. I endeavoured to convince them of the ill consequences that would ensure upon the measures they were taking, that instead of having their grievances redressed which they complained of, they were pursuing steps that would tend to the ruin of the Province: but all to no purpose, they insisting that the measure were peaceable, and that nothing would satisfy the Assembly unless I resigned, and that they would not answer for the consequences if I did not. Thus surrounded on every side, without any protection, I found myself under a necessity of complying, and prepared and signed a resignation … The Committee then insisted that I should go with them to the main Body, and there read said Resignation, which I at first refused to do, but there came several messages from the Body telling me that the People would not be satisfied unless I appeared before them, at the same time giving me assurances that I should meet with no insult. I was then escorted by the grand Committee to the main Body, who were drawn up in the form of a hollow square, and there was obliged to read said Resignation.

Judge Paine wrote that he had received no insult on this occasion other than having his hat knocked off, but local tradition asserts that his wig was knocked off as well, and that he picked it up and handed it to his slave saying, “Take this; I shall never wear it again.”

Dr. Paine had been waiting at Salem, intending to go to England in order to obtain a store of goods for the apothecary shop in Worcester. Upon hearing the news of his father’s experience with the mob, he sailed at once, not waiting for a brother who was riding down to see him. Embarked with the Doctor were three of his college friends, two Loyalists and Josiah Quincy, the official representative of the Massachusetts Whigs. They arrived in London in November, 1774, and the Doctor spent much of the winter which followed buying stock for the Worchester shop. In March, 1775, he sailed for Boston, where he found the evacuation of the British army in progress. Some friends said that he simply transhipped without setting foot on shore, but the Worcester newspaper reported that on May 3 the Doctor and one of his cousins had arrived at Salem. In either case, he was back in London in June, where he joined the circle of refugee American physicians and their English fellows, dining occasionally with Thomas Hutchinson, the former governor of Massachusetts.

On October 19, 1775, General Sir William Howe appointed Paine apothecary to the “Detached Hospital, North America.” Perhaps this job required an M.D. degree; at any rate, Paine obtained one, a month later, from Aberdeen. Presumably he submitted his application by mail, accompanied with the usual fee and recommendations as to his professional accomplishments. He sailed for New York with enthusiasm for his cause, for he wrote, “The Colonists had better lay down their arms at once, for we are coming from an overwhelming force to destroy them.” This proved to be a misapprehension of the situation. For several years he served as an apothecary to the army in New York and Rhode Island, where he attracted attention chiefly by acting as director of a lottery in behalf of the Loyalists.

In February, 1781, the Doctor sailed from New York for Lisbon in the capacity of private physician to Lord Winchelsea. The diary which he kept for his wife’s perusal is concerned largely with his worry about his debts. In June, he was again in England where he was admitted a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians, and where he soon developed a practice in high social circles. Fittingly, he was presented to the King. Few native Americans could, however, be happy in a society so unlike that in the colonies, and it was with pleasure that Doctor Paine accepted appointment by Sir Guy Carleton to the position of “Physician to the Army” with assignment to the hospital in Halifax.

At the moment, Dr. Paine did not have much inclination to return to Massachusetts. He had been proscribed as an absentee and his property confiscated by the Massachusetts act of 1778. The newspaper advertisements for the sale of his belongings dwell particularly on his fine mahogany furniture and his medical library, which had been gathered in London and was exceptional for its day. The story of the disposal of his confiscated property is typical of the experience of the absentee Loyalists. Their fellows who remained in New England were not troubled by the States, whose officials looked the other way while friends and relatives of the absentees recovered at least their personal property to keep for them. Judge Paine thus spent most of the war years quietly salvaging the property of his Loyalist friends and relatives. This apparently included the Doctor’s library, which is now in the American Antiquarian Society, and his silver, which is in the Worchester Art Museum. He did lose property valued at ₤2238, mainly in connection with the apothecary shop.

In the excitement of 1775 some Worcester Whigs had proposed that Doctor Paine be hanged if he returned, but he was in no such danger. A Canadian lady recently walked into my office in Worcester and said that she was the first member of her family to return since an ancestor had been hanged as a Loyalist. I agreed that her ancestor may have been hanged, but I assured her that no Loyalist was executed in New England for his political views or for his participation in the war. A very few were very briefly imprisoned, but even they were not disfranchised. In spite of the sorry conduct of the Whig politicians before 1776, no civil war was ever carried on with more tolerance of the losing side than the Revolution in New England.

For the most part, the mistreatment of the Loyalists who remained in or returned to New England was verbal. When Judge Paine returned to his home after the Evacuation of Boston, he found that the militiamen who had been billeted in it had cut the throat of his portrait, but they were withdrawn when he said that he intended to live in the house. This was, however, uncomfortably near the town common, on which the soldiers trained, so he hastened to complete the fine mansion which he was building further out. The Doctor’s mother had been a petite and dainty blonde, and now that she had put on weight she walked the streets of Worcester with a defiant firmness. Once as she passed the guardhouse she head a soldier say, “Let’s shoot the old Tory.” She turned on him and said, “Shoot if you dare,” and marched off to register her complaint with the commanding officer. Once when a file of soldiers appeared at the Paine mansion, she planted herself in the doorway and defied them. When her childhood home was seized, the soldiers threatened to shoot her for her interference, and she defied them to do it. They never had to put her under surveillance, they said, because she was always to be traced by the thread of yarn along the street connecting the knitting in her hand with the diminishing ball in the last house which she had visited.

By 1782 the town of Worcester had begun again to elect Judge Paine to the committee to instruct the Representative, and in 1785 it chose him Moderator, the most respected office in the town government. Still Dr. Paine was not yet sure of his welcome home. His wife and daughters had spent the first years of the war with his parents. Levi Lincoln, a future governor of Massachusetts, hearing that the Paines were having a hard time economically, had spitefully suggested that the eldest daughter be put out to service. So Lois Paine had taken this girl and passed through the British lines to join her husband in Rhode Island.

On October 26, 1782, Dr. Paine took up his duties as “physician to His Majesty’s Hospitals in Halifax,” where he immediately had a sharp clash with his commanding officer, who resented his appointment. He was, apparently, the administrative officer of the hospitals, and his full accounts in the manuscripts in the American Antiquarian Society constitute an unique medical record. After a year, however, the hospitals were discontinued because of the withdrawal of the troops, and he was placed on half pay.

The next obvious step for Dr. Paine was to exercise his right to a grant of land, and he located his on the island of La Tête, in Passamaquoddy Bay. There he led the first party of settlers late in 1783, and in the spring he was still enthusiastic about it:

The Harbor of L’Etang, where it is proposed to build a Town, is decidedly the best in America. It is sheltered from all winds and accessable at all seasons of the year. Last winter was the severest ever known in America, yet at this place … they never saw any ice in the Harbour … I have reconnoitered the adjacent country, which at present is an immence Forest, with care and attention, It exceeds any part of New England that I am acquainted with.

He was certain that his island would “soon be a place of consequence and ultimately the principal Port in British North America.” The chief problem was, he said, to obtain cash with which to hire ships to carry his lumber to southern ports, and to buy cattle to stock his lands.

Although New Englanders are poor frontiersmen, Dr. Paine would have remained at La Tête had not his wife insisted that they settle in some town where their children might be educated. So in 1785 he joined the congenial colony of Loyalists, many of them fellow Harvard men, at Saint John. There he was immediately appointed Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Woods, commissioned a Justice of the Peace, and elected to the Assembly. In view of the work of Professor MacNutt and other Canadian historians, there is no need for me to recount here the story of the Doctor’s public career in New Brunswick, but I should warn that earlier writers confused him with another refugee Loyalist, William Pagan of New York.

It used to be said that grass would not grow where the Turkish foot had trod. In contrast it might be said that colleges sprang up in the footprints of the Puritans. One of the first acts of the settlers of Massachusetts Bay was to found Harvard College, and wherever the songs of Harvard and Yale went, north, west, or south, colleges sprang up in their footsteps. These men knew well that even the imperfect democracy of the communities from which they came could not survive without an educated public. If William Paine had not taken the first step to found the institution which has grown into this University, some other members of the group of Harvard graduates in the Province would have done so.

It was soon apparent that the line between the Province and the States was only political. In 1784, Paine paid a visit to his Orne relatives and to Dr. Holyoke at Salem, and the next year he accepted appointment as one of the New Brunswick Commissioners for the New England Company, a missionary organization seeking Indians to save and civilize. It has been assumed that there was something surreptitious about Paine’s final removal to New England because he did not mention his intention in his last official letter to John Wentworth, who as Surveyor General of the king’s Woods was his superior. Actually, the new States had no warmer friend or more hearty well wisher than John Governor of Nova Scotia. Wentworth was still a busy trustee of Dartmouth College, which but for his refusal would have been named Wentworth College, and both men were warm friends of John Adams. He would have approved Paine’s change of residence. In June, 1787, the Doctor received permission from the War Office in London and from Governor Carleton to move his residence to Salem, and in October, he went.

Although Dr. Paine was not as yet ready to relinquish his half pay and his British citizenship, he had sound reasons to return to the States. Mrs. Paine was again complaining about lack of opportunity to educate the children, but the real reason for the removal was economic. The Doctor could not live on the proceeds from his practice at Saint John, where a great part of the population was indebted to him but simply unable to pay. At this time he was in constant correspondence with his brother Nathanial about his Worcester debtors, for apparently his assets in that town had not been confiscated by the State. If he were in Massachusetts, there would be a much better chance of collecting, and the matter was becoming urgent because of the spreading bankruptcy among his debtors at this time. Finally, there was a very considerable inheritance of Orne family property in Salem which needed his attention. Politics was no bar to his return, for in that town the property of only one Loyalist had been confiscated.

In October, 1787, the Paines were settled among the aristocracy of Salem, which looked askance at only his East India tobacco pipe on which he drew the smoke through the tube eight or ten feet long.

The scars of civil war were healing rapidly. At the next election Judge Paine received a plurality of the votes for the Worcester seat in the Congress of the United States, his rivals being distinguished Whigs, one of them no less a popular hero than his classmate, General Artemas Ward, the first commander of the Continental Army. It took two run off elections and the furious efforts of the Whigs to keep the Old Tory out of Congress, and they could not prevent his being returned to the State legislature by an overwhelming vote.

After the death of Judge Paine in 1793, the Doctor moved to Worcester where he finished the family mansion, called The Oaks, which he had been building for twenty years. So at the age of forty-three he returned from his wanderings and settled down to a long life of service as a physician. His chief business interest was a directorship in the Boston branch of the Bank of the United States. As a British subject he could not hold public office, and as a typical Yankee he could not give up his half pay. One becomes a trifle cynical at his regular reports to the War Office in London that he would be happy to be employed again in His Majesty’s service. He watched the approach of the War of 1812 in distress, believing that the United States was unready for hostilities of any kind, but quite ready to get into the war on the wrong side. There is no loyal summons to service in the family papers, but tradition says that he resigned his half pay when re-called by the Army in 1812. He had just finished buying up his brother’s shares of the family farm, and to leave it all and go into exile again was too much to ask of human nature. In June, 1812, he applied for naturalization, and offered the town a site for a new town hall.

The War of 1812 erased the old lines between Whig and Tory. Isaiah Thomas, the Worcester publisher whose newspaper had been the principal voice of the New England Whigs, and had been the means of keeping Judge Paine out of Congress, had not become a conservative, and with Dr. Paine boycotted Forth of July celebrations as rallies of the Democratic party. In 1812 these men joined in founding the American Antiquarian Society, of which the Doctor was the first vice president. In the formation of this, the first national historical organization in the United States, they enlisted the aid of men like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and they set on its way the institution which now had the strongest collection of printed material relating to the history of the United States. Its library is at Worcester because in 1812 it seemed best to keep it at an inland town not likely to be burned by the British.

Dr. Paine was also active in the Second Church of Worcester, which occupied a peculiar place in the New England system. In Massachusetts every town was required by law to maintain a church and a school. Since every adult male, and sometimes widows with property, participated in the choice of a minister and the annual voting of his salary, there was little room for sectarianism. The churches were typically Puritan in that they used no creeds or confessions of faith, and generally allowed anyone who took exception to the wording of their covenants to qualify for membership by stating his personal beliefs in his own words. The normal pattern in New England was for those who desired more sectarian religion to withdraw from the town churches and form Anglican, Baptist, or Presbyterian organizations. Worcester was different in that the town church, because of the large Ulster segment of the population, was more inclined than most of Calvinism. So here, uniquely, it was the theologically liberal group which seceded and formed the Second Church, which soon became Unitarian. Dr. Paine had been a warden of Trinity Church in Saint John, and had attended the Episcopal Church in Salem, but for want of one of this denomination in Worcester, he threw his lot with the liberals. This was not inconsistent with his political Loyalism, because here he was trying to conserve Puritan liberalism against a growing denominationalism.

During the forty years of a Doctor’s life after his return from exile, he saw Worcester reach the sea by the building of the Blackstone Canal, and felt the hot breath of the steam locomotive which was to destroy the canal system. Perhaps he would have liked to flee from the industrial revolution, but now he was held in Worcester by roots like those of the great oaks which gave his mansion its name. A grandson described him there:

I can see Dr. Paine as he walked out to the piazza, an alert, well preserved old gentleman, careful of his dress, which consisted of a dark blue dress coat, and drab colored trowsers, with a bunch of seals hanging from his watch-fob, and on his head a beaver hat of drab color. His complex was fair, his hair was snow white, and was brushed back from his face and tied in a queue bound with black ribbon, which ended in a bow of the same.

This, then, was the man whose fingers planted the acorn from which this University has grown.

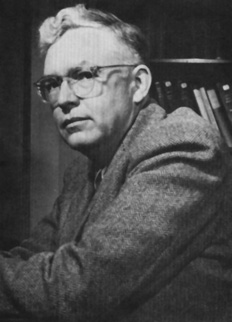

Clifford K. Shipton was a graduate of Harvard, holding the degrees of bachelor of science (1926), master of arts (1927), and doctor of philosophy (1933). From 1928 to 1930, he was, first, instructor in history at Brown University, then instructor and tutor in history at Harvard. He was named editor of Sibley Publications of the Massachusett's Historical Society in 1930 and in 1938 became the Custodian of Archives at Harvard, a part-time post in which he served until his retirement in 1969. Under Shipton, the archives' small and largely unrecognised collection grew to be one of the largest and richest in content of any university archives in the world. During this same time he also acted as librarian (1940) and director (1959) of the American Antiquarian Society, from which society he retired in 1967.

Clifford K. Shipton was a graduate of Harvard, holding the degrees of bachelor of science (1926), master of arts (1927), and doctor of philosophy (1933). From 1928 to 1930, he was, first, instructor in history at Brown University, then instructor and tutor in history at Harvard. He was named editor of Sibley Publications of the Massachusett's Historical Society in 1930 and in 1938 became the Custodian of Archives at Harvard, a part-time post in which he served until his retirement in 1969. Under Shipton, the archives' small and largely unrecognised collection grew to be one of the largest and richest in content of any university archives in the world. During this same time he also acted as librarian (1940) and director (1959) of the American Antiquarian Society, from which society he retired in 1967.

During his career, Dr. Shipton was a member and, in some cases, an elected officer of the the Massachusetts Historical Society; Colonial Society of Massachusetts; American Antiquarian Society; American Academy of Arts and Sciences; Society of American Archivists; Institute of Early American History and Culture; and the Beverly Historical Society (Honorary).

He was the author of 14 volumes of Sibley's Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Harvard College, classes 1690-1745; and biographies on Roger Conant (1945) and Isaiah Thomas (1947). In 1969 he co-authored, with James E. Mooney, the two-volume National Index of American Imprints Through 1800: the Short-Title Evans. He also published numerous articles on various aspects of colonial America, Harvard history, and the field of archives.

Dr. Clifford K. Shipton died on 4 December 1973.

Source: Holden, Harley P. "The Society of American Archivists - Deaths". The American Archivist 37, 3 (July 1974): 513-518.