By W. Stewart MacNutt

Professor of History

University of New Brunswick

Founders' Day Address

Thursday, March 6th, 1958

INTRODUCTION

These are days of crisis for Canada’s universities. The University of New Brunswick, like its sister institutions, is preoccupied with contemporary problems. Unprecedented numbers of young people are seeking admittance into our institutions of higher learning. Our philosophy of education challenges us to solve the problems of finance, staff and physical facilities to accommodate the demand.

These are days of crisis for Canada’s universities. The University of New Brunswick, like its sister institutions, is preoccupied with contemporary problems. Unprecedented numbers of young people are seeking admittance into our institutions of higher learning. Our philosophy of education challenges us to solve the problems of finance, staff and physical facilities to accommodate the demand.

But concentration on the present must not exclude re-examination of the past. The heritage and tradition of an institution give meaning and inspiration to its immediate existence and its future development. Professor MacNutt’s researches into the university’s past – which resulted in “The Founders and their Times” – is more than a re-examination. It is a re-assessment of history. The founders of this university, who were also the founders of this province, were, as Professor MacNutt makes clear in his treatise, “a badly abused set of men” and history has not done them justice.

Implicit in Professor MacNutt’s work lies the truism of historical evaluation: the actions and events of history must be assessed in the context of the times; the moral and ethical standards as well as the dictates of practical life must form part of the total picture. “The Founders and Their Times” is the most searching study to date of the lives and contributions of those men whose names are preserved on the original petition to which the University of New Brunswick owes its existence. It is a positive statement which dispels the opprobrium attached to their names by history.

Professor MacNutt’s final judgement on the founders of the university lends courage and strength at this time of crisis. As we face the problems of the present, this university can refer with pride to the faith and vision of its founders, who, with their successors, “were men of impulses just as generous and of wisdom after the fashion of their own times, just as great.”

Colin B. Mackay,

President.

The United Empire Loyalists of British North America have been a badly abused set of men. In their homeland, the thirteen colonies, the government of the American confederacy gave assurance on their behalf, but there were contemptuously ignored by the governments of the states. Even in Great Britain, for whose Crown they had suffered so much, a strong party arose in the House of Commons eager to frustrate many of their principal designs. Scarcely had they become established in their new homes on British soil when a new world conflict absorbed all the energies of the British Government upon which they so greatly depended to consolidate the remaining empire in North America on the principles they cherished.

To callow and superficial minds the almost uniformly successful career of the American Union has emphasized their lack of perspicacity and, especially in circles where there can be no pretensions to gentility whatever, their aristocratic predilections have been the subject of ribald slurs and plebeian humour. In New Brunswick, where they made their deepest imprint, those who followed the Loyalists envied their possession of the better lands and resented their pride in past sacrifices. Native historians have arisen to depict the Loyalist era as one of authoritarian politics and of hard-living, feckless men to whom the usurpation of power and privilege was almost a daily habit of life.

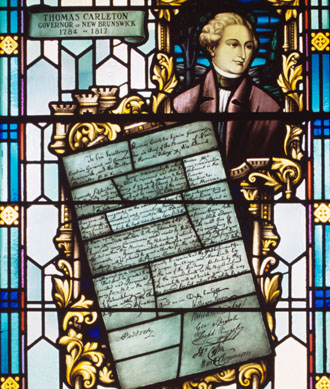

It is of the United Empire Loyalists that we must think tonight for the founders of the University of New Brunswick were the founders of the province. A glance at the charter of 1800 will very quickly show that the men who were charged with the destinies of the little college on Brunswick Street were those who, since 1784, had held the public offices of high responsibility. When we honour them we think not merely of an adventure in education. We think of that great schism of the English-speaking world, the American Revolution, and of the adventure in imperial reconstruction that followed it, of the men who came to New Brunswick faced with the task of creating a new province from what was almost virgin wilderness.

It was one of the virtues of the Loyalists that they favoured institutions of learning. Scarcely had Fredericton been selected as the capital of the province when late in 1785 a group of seven men came forward to suggest to Governor Carleton in a memorial that “an academy of liberal arts and sciences” should be established in the vicinity of the new town. The environment was not precisely favourable to education. Across the river from Fredericton the fields were fertilized with salmon and it was still possible, after the fashion of the Indians, to paddle stealthily from headland to headland along the front of the river and wait for the moose-deer, as they were called in those days, to come out of the forests for water. The sergeant-major of the 54th Regiment, William Cobbett, wrote almost lyrically of the delights of travel through the forest grandeur of New Brunswick and over its gently flowing streams. Patrick Campbell, who visited New Brunswick in 1792, declared his surprise on learning how his countrymen, the Highlanders of the Nashwaak, would each winter take to the woods with sleds and, after weeks of hunting and sleeping in the snow, would return to their habitations loaded with game of all kinds. The landed gentlemen of New Brunswick, with their back bowed with toil and their faces blackened by the smoke of burning bush, were settling down to the business of winning a competence. When they relaxed it was usually in the familiar outdoors, and the distant, fascinating retreats of the wilderness impelled them to a life that was roving and of irregular habits. Yet many of them were unable to abandon the pleasure of books and adventures of the intellect.

WILLIAM PAINE

The first signer and presumably the originator of the memorial was Doctor William Paine, a Loyalist of Massachusetts. An educated and exuberant man, he was a member of the first legislature for the country of Charlotte. His professions of enthusiasm for the future of the new province were numerous, one of the most notable being that the harbor of L’Etang was the finest in America. As a deputy surveyor of the King’s Woods he sailed up the Kennebecasis and, after passing Darling’s Island, the limit reached by a great forest fire of several years before, he found “the most delightful country on the face of the earth.” After inspecting the salt springs at Sussex Vale he could see glowing industrial possibilities for the region. But he could not sustain himself and his family on the prospects that he believed lay ahead. His half-pay of a discharged officer and the proceeds of his practice, he told Sir John Wentworth, were not enough. In 1787, on the expectation of “gathering up some property in New England,” he returned to his former home on leave of absence. Since he never came back to New Brunswick it is fair to assume that he was successful in this venture and that he made his peace with Mammon. This is no reason why we should fail to honour him for the significant and lasting influence he exerted while he was here.

The first signer and presumably the originator of the memorial was Doctor William Paine, a Loyalist of Massachusetts. An educated and exuberant man, he was a member of the first legislature for the country of Charlotte. His professions of enthusiasm for the future of the new province were numerous, one of the most notable being that the harbor of L’Etang was the finest in America. As a deputy surveyor of the King’s Woods he sailed up the Kennebecasis and, after passing Darling’s Island, the limit reached by a great forest fire of several years before, he found “the most delightful country on the face of the earth.” After inspecting the salt springs at Sussex Vale he could see glowing industrial possibilities for the region. But he could not sustain himself and his family on the prospects that he believed lay ahead. His half-pay of a discharged officer and the proceeds of his practice, he told Sir John Wentworth, were not enough. In 1787, on the expectation of “gathering up some property in New England,” he returned to his former home on leave of absence. Since he never came back to New Brunswick it is fair to assume that he was successful in this venture and that he made his peace with Mammon. This is no reason why we should fail to honour him for the significant and lasting influence he exerted while he was here.

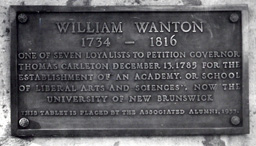

WILLIAM WANTON

The second signer of the memorial was William Wanton, the son of a former governor of Rhode Island. He held the important office of Collector of His Majesty’s Customs for the port of Saint John with jurisdiction over the entire province. Upon his arrival in 1785 he expressed surprise that the Laws of Trade and Navigation were in effect against the United States and, though he held his office for thirty years, he never did enforce the laws. Under his benevolent administration and that of his American counterpart at Eastport there developed in the quiet waters of Snug Cove, off the shores of Campobello, the most voluminous exchange of goods on this side of the North Atlantic. On conditions of mutual advantage Britons and Americans persuaded one another to break the laws of their respective countries. Because he functioned beneath the authority of the Lords of the Treasury in London, Wanton was immune to local persecution. When, after many years in which the illicit but popular trade flourished without flagging, the Colonial Office established effective liaison with the Lords of the Treasury upon this dubious form of prosperity. Wanton was, as they said, incredibly rich, incredibly fat and nearly eighty. In the polite society of Saint John he was notorious as a gourmet who, in his old age, had the good sense to become abstemious and there is nothing to indicate that he failed to finish his days in peace.

The second signer of the memorial was William Wanton, the son of a former governor of Rhode Island. He held the important office of Collector of His Majesty’s Customs for the port of Saint John with jurisdiction over the entire province. Upon his arrival in 1785 he expressed surprise that the Laws of Trade and Navigation were in effect against the United States and, though he held his office for thirty years, he never did enforce the laws. Under his benevolent administration and that of his American counterpart at Eastport there developed in the quiet waters of Snug Cove, off the shores of Campobello, the most voluminous exchange of goods on this side of the North Atlantic. On conditions of mutual advantage Britons and Americans persuaded one another to break the laws of their respective countries. Because he functioned beneath the authority of the Lords of the Treasury in London, Wanton was immune to local persecution. When, after many years in which the illicit but popular trade flourished without flagging, the Colonial Office established effective liaison with the Lords of the Treasury upon this dubious form of prosperity. Wanton was, as they said, incredibly rich, incredibly fat and nearly eighty. In the polite society of Saint John he was notorious as a gourmet who, in his old age, had the good sense to become abstemious and there is nothing to indicate that he failed to finish his days in peace.

Some of the signers of the historic memorial, all of whom are so splendidly commemorated by the class of 1905 in the Great Hall of the Arts Building, were men of comparatively inconspicuous fortunes. Of Zephaniah Kingsley we know nothing except that he came from South Carolina and owned land at Hammond River. George Sproule, a Loyalist of New Hampshire, was the first Surveyor-General of the province who labored faithfully at his task for thirty-four years. Adino Paddock, who had been surgeon to the King’s American Dragoons, gave almost a lifetime of professional service to the people of Saint John.

WARD CHIPMAN

Of all the signers Ward Chipman was probably the only one who made what might be called an illustrious contribution to the life of the province. The fastidious young bachelor who arrived at Saint John with Carleton, who could warble so acceptably for the entertainment of his friends, possessed a driving, imperious will as well as an acute legal mind. He wrote the charters of the College of New Brunswick and of the City of Saint John. He resoundingly demolished the American argument in the first two rounds of the boundary dispute, and, when he died, was masterfully delaying the settlement of the final round, seeking new expedients in a case that was nearly hopeless. The Americans may have won at last but they never got the better of Chipman.

Of all the signers Ward Chipman was probably the only one who made what might be called an illustrious contribution to the life of the province. The fastidious young bachelor who arrived at Saint John with Carleton, who could warble so acceptably for the entertainment of his friends, possessed a driving, imperious will as well as an acute legal mind. He wrote the charters of the College of New Brunswick and of the City of Saint John. He resoundingly demolished the American argument in the first two rounds of the boundary dispute, and, when he died, was masterfully delaying the settlement of the final round, seeking new expedients in a case that was nearly hopeless. The Americans may have won at last but they never got the better of Chipman.

For nineteen years, whenever Governor Carleton got into difficulties on civil affairs that could not be settled by military methods, Chipman was his right-hand man. In his old age, though a justice of the Supreme Court, he directed from behind the scenes the legislative struggle against Governor Smyth. When he died in 1823, the end of an era had come for he was the last survivor of the officials who had taken office in 1784. He had attained the greatest honour and the highest office the public life of an obscure colony could offer, that of President of the Council and Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty’s forces in the province.

JOHN COFFIN

Easily the most colourful and certainly the most martial of our memorialists was John Coffin, a sea-faring lad of Boston who volunteered for service with the royal forces on the day of Bunker Hill. On the ascent of that fire-swept slope his conduct was so fearless that he was awarded a commission on the field and throughout the remainder of the war he was famed as one of the most redoubtable of the cavalry commanders on the British side. At Eutaw Springs, at the head of seventy of the King’s American Dragoons, he shattered 300 of the enemy in an open fight, losing only three of his own men and killing sixty Americans – all with swords, for in the precipitation of the charge he had scorned to order his men to fire. Following the battle the rebel General Greene, though placing a price of $10,000 on his head, publicly pronounced upon his valour. When Charleston was occupied by the rebels he made an entrance to the city in order to visit the lady to whom he was betrothed and, according to a well-authenticated tradition, when his rendezvous was interrupted by a wary American patrol, he escaped capture by concealing himself beneath a hooped skirt though he was a man of six feet, two inches. Awarded a handsome sword by Lord Cornwallis in token of his distinguished services, he was a member of the advance guard of the provincial regiments that came to the Saint John River and superintended the clearing of land on the west side of the harbor of Saint John. Unlike most Yankees of his time he had a reverence for ancestry and tradition. On the banks of the Nerepis he purchased the estate of Beamsley Glazier and called it Alwington Manor, the name of a residence constructed by a Norman ancestor in Somerset on the shores of the Bristol Channel.

Coffin’s career continued to be remarkable for many years after he came to New Brunswick. He took the head of the Governor’s party in the legislature and finally routed and discredited a factious, obstructive opposition in the election of 1802. In those days high words in politics often led to affairs of honour and, on a raw day in February, 1797, he fought James Glenie in a duel with pistols in a wood across the river from Fredericton. Some of his political tactics were of the shock variety, as abrupt as the charge at Eutaw Springs. In the election of 1809, after thirty-eight electors of Kingston turned out to vote for Coffin, the sheriff at noon on the first day of the poll decided that no opposition had appeared and, though the statute said that the poll should be kept open for fifteen days, declared Coffin elected. “Thed did us complete out of our goose,” said the letter of “an old refugee” to the Royal Gazette, protesting the failure of the sheriff to consult the 400 other freeholders of King’s County.

In his old age, Coffin battled the overwhelming tendencies of the times, supporting what was called “the landed interest” of the country against the rising power of the mercantile classes. In the British House of Commons his cousin, Sir Isaac Coffin, was a leader in the fight to destroy the tariff preferences on British North America timber and John Coffin honestly believed that the newly risen timber trade, devouring the country like a plague of locusts and drawing off labour from the farms, would be the ruination of the province. Like a good member of the English squirearchy he believed in the settled, ordered life of villages and when he died in 1838, a full general in the British Army, he was, after the fashion of a good English landlord, buried in the parish church at Westfield.

THOMAS CARLETON

Thomas Carleton, who received the memorial, was not the kind of man who might be expected to favour educational projects. His career had been exclusively military and it was his habit to assert that he knew nothing of civil business. During the interval between the two great wars of his generation he had taken a reprieve from the King’s command and had served the Empress Catharine in south Russia against the Turks. Twice in the war of the American Revolution he had been wounded. His temper was chilly and guarded. His letters, terse and cryptic, are the despair of those who seek for what might be called human qualities. In their private correspondence with one another the officials of his government referred to him as “Our Friend.” If he were really as aloof from his subordinates as their remarks would indicate, this impression must have been powerfully fortified by the lady at this side who presided over the social scene at Fredericton for the first twenty years of its history. “Do you know,” wrote Mather Byles in a letter to Ward Chipman, “the reason why Mrs. C. doesn’t like to ride in a sleigh with two horses? She thinks that two horses look sociable and she hates anything that looks sociable.”

Thomas Carleton, who received the memorial, was not the kind of man who might be expected to favour educational projects. His career had been exclusively military and it was his habit to assert that he knew nothing of civil business. During the interval between the two great wars of his generation he had taken a reprieve from the King’s command and had served the Empress Catharine in south Russia against the Turks. Twice in the war of the American Revolution he had been wounded. His temper was chilly and guarded. His letters, terse and cryptic, are the despair of those who seek for what might be called human qualities. In their private correspondence with one another the officials of his government referred to him as “Our Friend.” If he were really as aloof from his subordinates as their remarks would indicate, this impression must have been powerfully fortified by the lady at this side who presided over the social scene at Fredericton for the first twenty years of its history. “Do you know,” wrote Mather Byles in a letter to Ward Chipman, “the reason why Mrs. C. doesn’t like to ride in a sleigh with two horses? She thinks that two horses look sociable and she hates anything that looks sociable.”

Yet, if we have a single founder it was this remote man of few words and soldierly habits. He established the “academy of liberal arts and sciences,” and he looked forward to the time when it should develop into an institution of higher learning, performing the role of a university. The idea of a university was very much in the wind, for Bishop Inglis had already procured imperial support for the establishment of King’s College at Windsor and provincial pride had become aroused at the suggestion that New Brunswick should take second place to Nova Scotia.

In the minds of the Loyalists of this province Nova Scotians were a contemptible breed of men. To the soldiers who had fought and suffered during the long war the citadel at Halifax had been “a Camp of repose.” To the men skilled in civil affairs the officers of government at Halifax were a gang of avaricious Scots and unprincipled Yankees who had grown rich from the events that had resulted in their own ruin. The people of New Brunswick, Carleton told the Colonial Office sharply, would require proof that no preference should be given to the elder province. Though Bishop Inglis, in his zeal for centralizing education in British North America, was able to delay imperial consent for ten years, Carleton finally won his case. A royal charter for the College of New Brunswick was finally granted on February 12, 1800. In spite of a considerable amount of experience that suggested the contrary, it was still an article of faith that the proprietorship of land in New Brunswick was a guarantee of affluence, and a magnificent grant of six thousand acres to the south and east of Fredericton was set aside in order to yield a revenue for the new university. Just as in later years, the provincial government was generous with its bounty, the only form of assistance it could offer at this time.

In the beginning New Brunswick had shown signs of developing along the lines Carleton had planned for it. His idea of colonization was really a Roman one, that new settlements would grow up in the shadow of fortified enclosures, that legions of armed men would be necessary to protect the frontiers of settlement against the still dangerous Malecites of the upper Saint John. He had accepted the governorship of the province only on the condition that the two regiments should be placed at his disposal and he had chosen Fredericton as the capital because it was the best military base from which the advance of settlement to the north could be controlled.

After 1790, when the 8th Regiment arrived to join the 54th, he had two good years. Nearly a thousand men paraded the precincts of Government House. Grand Falls and Presqu’ile became the sites of garrisons whose duty it was to protect the settlers and guard the debatable frontier with the Americans. The troops were popular because they brought hard cash to an infant economy where it was in scarce supply and casual labour, an equally scarce commodity, to the farms of Loyalist gentlemen. In this bracing and martial environment Carleton was happy. He enjoyed the military command in the two provinces and once each year he proceeded to Halifax to inspect the troops of the fortress and to impress upon the alien government of Nova Scotia the deeply cherished Loyalist idea, that New Brunswick was the heart and core of the British Empire in North America.

Suddenly all of the happy auspices that promised a fair future for the colony were dispersed. Early in 1793 Great Britain entered upon a war of twenty-two years with the French Republic and Empire, and New Brunswick became an orphan in the storm. The two British regiments of the line left the province, one for the West Indies, the other for Halifax. Carleton instantly became unhappy. The only reason troops were required in Halifax, he told the War Office peevishly, was to protect the naval stores against the local population. Lord Dorchester, the elder brother of Carleton, upon whom the Loyalists relied so strongly, fell into disgrace with the British Government owing to his premature preparation of the Indians of the west for a war against the Americans. Insurance rates rose against British shipping and, in order to supply the West Indies cheaply and regularly with the goods of North America, the imperial authorities admitted to their markets the shipping of the United States. The quick consequence of this wartime measure was that Saint John’s sixty sail of square-rigged vessels disappeared from the seas.

CARLETON LOSES INFLUENCE

In consequence of the war Halifax became the warden of the north. Carleton lost his influence at London and a new governor of Nova Scotia, Sir John Wentworth, gave advice on all the affairs of British North America. When Edward, Duke of Kent, arrived at Halifax to take command of the troops in both provinces Carleton’s cup of private sorrows was filled. To direct the purely civil affairs of a community of less than twenty thousand people was a task inconsistent with his character and training, especially when broad currents of discontent were blowing close to home. The war caught up the energies of the young men of the country and the scarcity of farm labour became more acute than it had been before. A decline in the value of real estate appeared to many as sure proof that the whole Loyalist experiment in New Brunswick had drastically failed.

Out of the past had come the dark, avenging figure of James Glenie, a Scots officer of artillery, upon whom Carleton, as a member of a board of court-martial nearly twenty years before, passed sentence of dismissal from the King’s service. With a mixture of malice and mischief, cogent common sense and extravagant language, Glenie became the political hero of Sunbury County, the head of a rag-taggle opposition in the legislature that eventually gained control, defeating many of Carleton’s projects and stultifying his plans for the development of the province. The grand Loyalist virtues of discipline, unity and obedience, so loudly proclaimed by their leaders, had given place to an undignified and unsalutary exhibition of party division, public and private despair, and of scrabbling quarrels for the few hundred pounds that made up the provincial revenue.

When Carleton sailed for England in 1803 he was a disappointed man. The province had failed to develop and its population was static. The north was still an unoccupied waste. There was no immediate prospect for the return of New Brunswick to imperial favour and the college, for which he had obtained a charter, had not risen on the wooded slope above Fredericton.

He and all the generation of the founders have received what in our day would be called a very bad press. The historian of New Brunswick, James Hannay, lived in a rarefied and virtuous environment, and he did not hesitate to apply to the problems and personalities of another age his own set of exalted values. He professed the Liberalism of Laurier, so triumphant and so enlightened. He voiced the austere standards and honest pride of the Kirk of Scotland of which he was a member. He volubly reflected the abounding ambitions of the merchants of Saint John where Carleton had never been forgiven for the establishment of the capital at Fredericton. His pages growl with rancor against those who had the conduct of New Brunswick affairs in their hands at this time and he takes no care to guard himself by reservations in the employment of expressions such as “the despotic character of the Governor and his friends.”

A NAME OF HONOUR

Hannay’s interpretation of the founders and their times has rather uncritically been passed into the writing of Canadian history so that the politics of New Brunswick have acquired a national reputation for being horny-handed, patriarchal, mysterious. That unhappy term of abuse, ‘Family Compact,’ imported from Upper Canada where in turn it had been imported from the political vocabulary of eighteenth century Europe, has been tossed about from one careless author to another, though the manifold facts of New Brunswick history will show that family compacts, an invariable ingredient in the politics of a small society, are just as frequently to be found in opposition as in office.

It is not possible here to defend Carleton in detail upon all his conduct in a struggle between the royal prerogative and popular privileges, between British procedures and colonial precedents, between a so-called aristocracy and those who professed to speak for the toiling masses, but common decency impels one remark. On May 18, 1833, the City Corporation of Saint John gave a great public dinner to the surviving Loyalists and their children in order to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Loyalist landing. It was a time of intense excitement for public opinion in New Brunswick had been aroused as never before. The brig Caledonian had just cleared the harbor, bearing Edward Barron Chandler and Charles Simonds, the delegates sent to London by the legislature to protest the management of the Crown Lands. It was a poor season for despots, but, to the air of “the Dead March in Saul” the memory of “good Governor Carleton” was toasted and speaker followed speaker to attest to his virtues. It was recalled with feeling that during his nineteen years in New Brunswick he had never collected a single penny of the fees to which he was legally entitled for the granting of lands. He had left the province thirty years before and had been dead for fifteen. He had no descendants and no close friends in the province. His administration had long been a closed book. But at this time, when the rights of the people was the cry of the leading politicians of the province, what had been said so frequently in his lifetime was said again, “that the name of Carleton is a name of honour.”

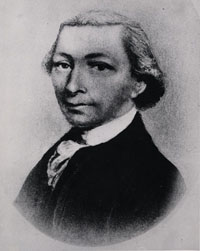

JONATHAN ODELL

The memory of Jonathan Odell, a member of the original Board of Trustees of the College of New Brunswick, has suffered from much the same reason. The fact that the and his son held the secretaryship of the province for sixty years has often been suggested as another evidence of the nepotism and injustice that flourished under the old colonial system. The true statement of the case is that in 1808, after twenty-four years of service to the Crown in New Brunswick, Jonathan Odell feared poverty in his old age. From his small salary as Secretary he had paid the wages of his clerks and the cost of firewood for his office. After fifteen years of inflation, in which prices had more than doubled, his salary had been unchanged from the figure at which it had stood at the establishment of the province. Had it not been for the saving of a little property in New Jersey he would have faced hopeless embarrassment. He therefore asked that for the continued support of his three daughters, two of whom were unmarried, his son, William Franklin Odell, should be permitted to succeed him in his office. The Colonial Office replied that on general principles this was objectionable but, after two refusals, agreed in 1811 that the succession should be permitted.

The memory of Jonathan Odell, a member of the original Board of Trustees of the College of New Brunswick, has suffered from much the same reason. The fact that the and his son held the secretaryship of the province for sixty years has often been suggested as another evidence of the nepotism and injustice that flourished under the old colonial system. The true statement of the case is that in 1808, after twenty-four years of service to the Crown in New Brunswick, Jonathan Odell feared poverty in his old age. From his small salary as Secretary he had paid the wages of his clerks and the cost of firewood for his office. After fifteen years of inflation, in which prices had more than doubled, his salary had been unchanged from the figure at which it had stood at the establishment of the province. Had it not been for the saving of a little property in New Jersey he would have faced hopeless embarrassment. He therefore asked that for the continued support of his three daughters, two of whom were unmarried, his son, William Franklin Odell, should be permitted to succeed him in his office. The Colonial Office replied that on general principles this was objectionable but, after two refusals, agreed in 1811 that the succession should be permitted.

Professor A.R.M. Lower, a leading exponent of the nationalist school of Canadian historical writing, who liked to think of Canada as a rising phoenix-like in the twentieth century into “the fresh air of North America” from the ashes of an invidious colonial past, writes of the men who surrounded Carleton as “the grandees of the Loyalists.” Whatever images of grandeur they may have had, they cultivated their own gardens. Judges of the Supreme Court took to agriculture. The first generation of Loyalist officials encountered, in most cases, nothing but disappointment. Edward Winslow might have spoken for almost all of them when he said, “I must go up to Heaven to shake hands with Lazarus, for damn me if there is any man in this world poor enough to keep me company.”

The Honourable and Reverend Jonathan Odell was one of the most capable men who served on the British side in the Revolutionary War. As missionary at Burlington and Mount Holly in New Jersey he had, at the very opening stages of the struggle, become an object of suspicion to those who presumed to represent the popular point of view. In October, 1775, when one of his letters was intercepted, he was arrested by order of the provincial congress of New Jersey. On December 12, 1776, after he had been held for over a year under protective custody within the limits of his parish, a party of armed men with fixed bayonets landed from a rebel galley in front of Burlington for the express object of seizing his person. There was a house-to-house search, but, screened by his parishioners, he bolted for the British lines at New York.

There his talents were of service. He joined in the war of ideas, directing a flood of satiric propaganda to the great mass of the American people who were basically neutral in the struggle, pouring scorn upon the unworthy motives and hypocritical explanation that characterized the conduct of the Continental Congress. Late in the war, by reason of sheer competence, he became translator of French and Spanish documents to Sir Guy Carleton. We catch a glimpse of him as chaplain to the King’s American Dragoons at their camp at Fresh Meadows, Long Island, on the occasion when Prince William reviewed the regiment and the soldiers, on their knees with their helmets in their hands and their swords by their sides, swore an oath of eternal loyalty to their sovereign and to their standard. Owing to the gratitude of Sir Guy Carleton for his multifold services, he became the first Secretary for the province of New Brunswick. he was a little man with sharp features and his letters, even if they are official, are invariably brisk and cheerful, displaying a cultivated affinity for the Latin epigram.

For sixty years the Odells, father and son, performed the workaday routine of New Brunswick government, having a hand in almost every administrative detail that passed over the Governor’s signature. Today the men are gone but the name remains – or a corruption of it remains. Perhaps, owing to the vogue for Irishry the city government of Fredericton has permitted the name to be spelt with an apostrophe. For the purposes of popularization and advertisement the amendment may be justified, but it is an act of bad faith to the memory of the men who did so much for the province in its early days.

THE LUDLOWS

The names of the Ludlow brothers of Long Island, both men of mark on the Loyalist side in New York, are found on the list of our founders. George Duncan Ludlow, the first chief-justice of the province, had been employed as supervisor of police on Long Island while it was under British occupation. Attainted by the state legislature of New York, he was an especial object of rebel vengeance and in 1780 a party of armed men who had crossed Long Island Sound to take him prisoner burnt his house to the ground when they failed in their purpose. Judge Thomas Jones, a Loyalist historian, though admitting that Ludlow was liberally educated, described him as “the little tyrant of Long Island” who favoured his friends with all the influence at his command. There is little in his later New Brunswick career either to substantiate or discredit this statement.

The names of the Ludlow brothers of Long Island, both men of mark on the Loyalist side in New York, are found on the list of our founders. George Duncan Ludlow, the first chief-justice of the province, had been employed as supervisor of police on Long Island while it was under British occupation. Attainted by the state legislature of New York, he was an especial object of rebel vengeance and in 1780 a party of armed men who had crossed Long Island Sound to take him prisoner burnt his house to the ground when they failed in their purpose. Judge Thomas Jones, a Loyalist historian, though admitting that Ludlow was liberally educated, described him as “the little tyrant of Long Island” who favoured his friends with all the influence at his command. There is little in his later New Brunswick career either to substantiate or discredit this statement.

His brother Gabriel was a man of arms. On the great day in July, 1776, when the British army under Sir William Howe landed on Long Island and drove Washington’s army in pell-mell flight to the mainland, he led seven hundred loyal men of Queen’s County to join the royal forces at Jamaica Plains. For a considerable time he commanded de Lancey’s Brigade and throughout the war his house at Hampstead was a favourite resort of British officers and Loyalist gentlemen. He came to New Brunswick as senior councillor with a prestige second only to that of Carleton himself.

The charter of 1800 shows the names of two assistant judges of the Supreme Court, Isaac Allen who had commanded the second battalion of New Jersey Volunteers and John Saunders, a captain in the Queen’s American Rangers. As one of the most renowned of Loyalist partisans in Virginia, Saunders especially had had a notable military career. At the capitulation of Yorktown so fearful were he and his regimental commander, John Simcoe, of rebel vengeance upon their persons that, contrary to the laws of the war, they made their way out of the town on a hospital ship before the formal surrender. Of all the Loyalists who came to New Brunswick he made the most intense effort to found a great landed estate on the pattern that was so highly esteemed in the eighteenth century. He was the founder of The Barony and when he died he was easily the greatest landowner in the province. Yet the Barony never became the equivalent in value of the smaller but more fruitful property he had left behind in Princess Anne County in Virginia. There, according to the memorial he submitted to the Loyalist Commissioners, he had possessed eight hundred acres of fertile land, orchards of apples and peaches, twelve negro slaves, a still of good oak timber and a home that was famed as the most hospitable in the county.

THE TWILIGHT OF THE FOUNDERS

Most of the founders passed from the scene before the academic institution they had sponsored achieved the role of a university. Provincial pride never faltered but all the terms of trade and the pronouncements of high policy did not favour the development of New Brunswick in their times. Sheep grazed on the greens at Fredericton and Carleton’s capital, the metropolis of the province as they called it, acquired the external attributes of a dreamy and remote hamlet. In Saint John, there were frequent and irreverent references to “the aristocracy of a provincial village.” Year after year the obituaries printed in the Royal Gazette reminded the founders and their contemporaries of the hazards of their early life. Some gloried in the memories of the dubious victory at Eutaw Springs and the magnificent defence of Fort Ninety-Six. Others could recall the disasters at King’s Mountain and the Cowpens. There had been the war of whale-boats on Long Island Sound and a few had lived through the loathsome experience of the hideous rebel prison at Sinsbury Mines. The same pages tell of the great events in the world from which their new and adopted country was far removed, Camperdown, Salamanca, Waterloo, the storming of Fort Erie by the gallant 104th.

Yet a few survived to see the coming of better times and the realization of the idea that had been conceived in the first, hopeful days of the province. In 1811 a jingle in the Royal Gazette announced that formerly the hero had been decked with laurel but that now he would be adorned with pine, “an unfading wreath from New Brunswick Pine.” Half a dozen favourable events occurred in many years to revive industry and bring new people to New Brunswick, but easily the most important of these was the opening of the great British market for commercial timber to the produce of the province. Scottish merchants who had formerly cruised the forests of Poland and Finland, who had dealt in the great marts at Danzig and Memel, came to the Miramichi and the effective settlement of the North Shore really commenced.

From the Crown Lands revenues poured so profusely that the government was able to animate activity of all kinds in the province. One of the great consequences was that the new prosperity of the province was crowned by a university. King’s College was constructed from “the rough stone of the country,” but it was paid for in squared timber, the staple commodity upon which the economy of the province was now so firmly based. Sir Howard Douglas who presided on the happy occasion of its opening on New Year’s Day, 1829, though injecting a tremendous amount of his own talent and energy into the realization of the grand idea, was in many respects the heir to the patrimony of Carleton and his contemporaries who had never abandoned the idea of a university through all the disappointing years.

NEVER SECTARIAN, ALWAYS PROVINCIAL

If I may conclude this paper on a mild note of querulousness, there is one other set of circumstances concerning the work of the founders to which I shall refer. When Thomas Carleton secured the royal charter for the College of New Brunswick in 1800 it provided the President and other persons in authority should be members of the Church of England and that services of the Church of England should be held twice daily within the precincts of the College. These stipulations were entirely acceptable to the vast majority of the people of New Brunswick at the time. Before the Loyalists had left New York they had nearly all, according to a dispatch of Sir Guy Carleton, announced themselves to be members of the Church of England and, in accordance with this consent freely given, the Church of England became established by law in the province. Yet tendentious writers, reflecting the prejudice of a society of which they themselves have been members in later years, have seized upon the charter of the College of New Brunswick as another evidence of the autocratic character of Thomas Carleton and the tyrannic impositions of an erastian church.

Outraged Anglicanism has never really answered back. But it should be recalled that it was not for many years after 1800 that the Wesleyan movement acquired the identity of a separate church. It was not until about 1825 that the Baptist congregations, springing so miraculously from the frontier communities of New Brunswick, exhibited the form and demeanour of a church organization. The Kirk of Scotland, though always formidable, did not arrive upon the scene until long after the province was founded. The dusty records of the Colonial Office at London contain a long series of urgent requests from the lieutentant-governor of New Brunswick for clarification of the position of the Church of Scotland in the colonies, especially with respect to its privileges and its legal status. These were invariably referred to the law Officers of the Crown, but these functionaries never found it either politic or expedient to give an opinion upon this awkward problem.

The loss of the outward show of religious unity severely compromised the position of King’s College as popular control over the government of New Brunswick became more certain in the middle years of the nineteenth century. Forty years after the first granting of the charter it could be fairly asserted that it had been made for the requirements of another age. The second generation of New Brunswickers, though they retained their political loyalties, had become enthusiastic sectarians in religion.

A devout Presbyterian from The Land of Cakes who visited Saint John about 1828 was surprised to find that religious fervor in the Old Land had been outstripped by that of a young colony, that the favourite subject for speculation at dinner-parties in Saint John concerned the rival merits of prepared and impromptu praying. The same visitor remarked that the Kirk of Scotland in the Atlantic Provinces was like an inner court of God, a kind of offensive and defensive alliance. If this were really so it must surely have been in emulation of other Protestant denominations whose sense of superiority was no less certain. Overshadowing the rivalries that were so strident amongst the Protestant section of the population was the rapid growth of the Roman Catholic Church whose distinctive points of view were becoming more prominent.

For fifteen years, between 1845 and 1860, King’s College constituted one of the major political problems of the province, the object of denominational rivalry and party strife. Change comes slowly. It is difficult to arrive at a decision to change the character of a long established institution and having agreed upon the necessity of change, it is often still more difficult to determine what kind of change should be made. In 1800 the common ground on which men had been able to meet was that the provincial university should come under the direction of the established church of the land. In 1859, when sectarian jealousies were acute, when even the gentle and civilized Anglicans were at one another’s throats, the only common ground on which men could meet was that the provincial university should offer no privilege to any church and that no religious instruction should be permitted within it. This was the great conclusion achieved by the most eminent men at that time, Samuel Leonard Tilley, Lemuel Allen Wilmot and John Hamilton Gray.

Over sixty years a great change had taken place in the cultural and religious complexion of the people of New Brunswick. Yet when we read the great plea for the University of New Brunswick made by John Hamilton Gray in the legislative debates of 1858, “not a local college, not the college of Fredericton, Saint John or Sackville, not the college of this sect or that sect, but open and free to the whole country,” it is possible to reflect that the and his contemporaries were expressing aspirations that were not substantially different from those of Thomas Carleton and the original founders, who were men of impulses just as generous and of wisdom, after the fashion of their own times, just as great.

On Monday, February 9, 1976 W. Stewart MacNutt died in the Victoria Public Hospital, Fredericton, after a long illness. He was a widely known and respected historian; a distinguished author and teacher; a man who gave much to UNB.

What follows is a tribute to Prof. MacNutt read into the Senate minutes of Feb. 10 by Alvin Shaw, acting dean of arts.

The Senate of the University of New Brunswick pays tribute to a former member, one whose many contributions to this institution have earned for him our respect, admiration and affection.

William Stewart MacNutt was born and raised in Prince Edward Island, educated in the Atlantic Provinces and the United Kingdom, taught school, served in the Canadian Army and while still on overseas duty, taught at Khaki University. In 1946, upon retirement from the Canadian Army with the rank of captain, he joined the faculty to begin a thirty year association with the University of New Brunswick. A distinguished scholar, he was the recipient of an I.O.D.E. Overseas Scholarship, a Nuffield Fellowship, a Canada Council Fellowship and a Killam Committee Fellowship, and was named a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

William Stewart MacNutt was born and raised in Prince Edward Island, educated in the Atlantic Provinces and the United Kingdom, taught school, served in the Canadian Army and while still on overseas duty, taught at Khaki University. In 1946, upon retirement from the Canadian Army with the rank of captain, he joined the faculty to begin a thirty year association with the University of New Brunswick. A distinguished scholar, he was the recipient of an I.O.D.E. Overseas Scholarship, a Nuffield Fellowship, a Canada Council Fellowship and a Killam Committee Fellowship, and was named a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

In a life given over completely to the cause of humanism, it is not surprising that Stewart MacNutt was, for a long period of time, closely linked with the Humanities Association of Canada. A member of the national executive committee for many years, he served as national president from 1965 to 1967.

After many years of outstanding service as a consummate instructor in the department of history, where his preparation, his presentation and his qualities of mind earned for him a brilliant reputation among many generations of students, he yielded to the appeal of his colleagues to become the second dean in the history of the faculty of arts, a post which he filled with devotion, skill and leadership during the often turbulent years of 1964 to 1970.

However, Stewart MacNutt's other accomplishments grow pale in comarison to his contribution as a publishing historian. An author whose grace and style make exposure to his work a pleasure and whose obvious intellect captures the reader, he has become the outstanding authority on the history of the Atlantic Provinces of Canada. From his pen has flowed an extensive series of writings which are, at one and the same time, a glowing testimony to present ablility and an imperishable memorial for the future.

Associated with this must be his fine contribution to the programme for Loyalist studies and publications. The former Canadian chairman of the programme and its guide and mentor on this campus, his dedication to the task, his meticulous research and his creative insight are, in large part, responsible for its present and continuing success.

The Atlantic Provinces have not failed to recognize his worth; St. Thomas University, Dalhousie University and the University of Prince Edward Island have awarded him the doctorate. The University of New Brunswick, that institution which he adopted, which he made his own and which he crowned with his laurels, has accorded him double honour by naming him professor emeritus of history and awarding him the doctorate.

Scholar, author, humanist, professor and administrator, Stewart MacNutt has served the University of New Brunswick with skill, detailed attention and love. The University community bids a sorrowful and affectionate farewell to an old friend.

Source: "University mourns yet another loss." University Perspectives 2,12 (16 February 1976): 2.