Getting Started

Knowledge synthesis is a type of research that evaluates and summarizes all available evidence on a particular topic through comprehensive literature searches and advanced qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods. The process includes study types like systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses, and clinical practice guidelines.

Evidence synthesis is a form of research that includes dozens of types of reviews that all share a set of core methodologies, and that (in addition to systematic reviews) also includes umbrella reviews, clinical guidelines, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses, and more. The purpose of an evidence synthesis is to take all the available evidence on a topic and draw conclusions based on the amount and strength of the evidence available.

Knowledge syntheses share three fundamental traits. They are:

- Comprehensive: They capture all the available research across many sources, often with the assistance of a trained information professional like a librarian

- Transparent: Every step and decision is recorded and described in the end report or in an online appendix

- Replicable: Sufficient detail is provided that another researcher could repeat the process and come out with identical or very similar results

Different disciplines have different types of knowledge synthesis. The main categories of review types are: systematic, scoping, rapid, umbrella, and meta-analysis. Within these categories are various specific kinds of reviews depending on what you’re trying to do, and each may have different guidelines/methods for conducting the review.

- Knowledge Synthesis Decision Tool

- St. Michael’s Hospital: Right Review

- University of Manitoba: Which review is right for you?

- Article: Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements

- Article: On empty, redundant or pointless systematic reviews

Undertaking a knowledge synthesis is a big commitment and here are a few key things to consider:

- Time: This type of research can take anywhere from 9-24 months to complete depending on the topic and team availability. A literature or rapid review are options if you can’t commit to this length of time.

- Team: This research cannot be done alone. Your team should have a minimum of 2 people, but ideally more depending on the needed expertise. For example, at least one person should be familiar with the review methodology, a statistician should be involved when doing a meta-analysis, and it’s strongly recommended to involve a librarian either directly as a collaborator or through consultation.

- Guidance: Is there a standard, handbook, manual, or something to guide your chosen method? If so you should adhere to this guidance to ensure your work is transparent and reproducible.

- Tools: You need to consider which tools are available to you for this type of research and which ones you may need to get access to. This can include choosing a citation management program (e.g. Zotero, Endnote), screening tool (Covidence, etc.), and data analysis.

For a more detailed checklist, please see our Knowledge Synthesis Readiness Checklist.

Preparation

The preparation stage of knowledge synthesis projects encompasses all the work that goes into deciding on and defining the topic you wish to review. This includes forming your research question, checking to see if there are any existing reviews on your topic, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria for your question, registering your protocol, and doing an initial search on your topic to ensure that there is sufficient research available to perform a successful review. In this section, we briefly break down these steps and offer outlines of what they involve as well as links to vital resources in their successful completion.

A research question for a knowledge synthesis should be made up of three to five distinct components (such as the primary issue, outcome, and/or context), with the precise number of components being dependent on the type of review you are doing and the amount of research that is available on your topic. Depending on your discipline of study, you may also find that there are suggested guidelines for what the specific components of your research question should address, but, unlike other steps in knowledge synthesis, the guidelines for question formation tend to be flexible and serve more as suggestions than actual rules.

In forming your research question, it may be helpful to review suggested guidelines for your discipline, like:

Once you have decided on a research question, it’s important that you check to find out if your topic has been done before or not, and if it has, to determine whether if an update to the existing review is needed / justified.

In looking for existing reviews on your topic, here are some places to consider:

- Knowledge synthesis organizations like the Cochrane Collaboration, the JBI Protocol Registry, the JBI journal itself**, and the Campbell Collaboration. There are also others spanning different disciplines and research areas if your topic falls outside of the health sciences.

- Government organizations like National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE in UK), Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology (CADTH in Canada), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (ARQH in USA), Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Germany), and Haute Autorité de Santé (France).

- Knowledge synthesis registries like PROSPERO for knowledge syntheses that are in progress but have not yet been completed / published. JBI also has a registry that is publicly available.

- Disciplinary databases like Pubmed, EMBASE, Scopus, TRIP, and Systematic Review Data Repository.

- SR / KS focused journals like BMC Systematic Reviews or BMJ Open.

** The JBI journal is best searched using either PubMed or CINAHL as an interface. JBI articles can be identified by using the following search strings:

- CINAHL: JN("JBI database of systematic reviews & implementation reports" OR "JBI library of systematic reviews")

- PubMed: ("JBI database system rev implement rep" OR "JBI Libr Syst Rev" OR "JBI Evid Synth")

The inclusion criteria (which can also be framed as exclusion criteria in some reviews) are the guidelines that reviewers follow when determining whether a specific item is relevant in the precise context of the question being asked. These criteria should be rigidly adhered to and constitute a promise to the readers by the reviewers that only the items that fit all the criteria were included in the review.

Some common inclusion criteria include:

- Details of a population under consideration

- Details about the nature of the phenomenon, context, or action being considered

- The types of studies / resources being included in the review.**

**The specific contents of this section vary widely between the types of syntheses and even within types as it is influenced by the amount and types of research available on the topic. Additionally, this is another section where the criteria may be a little more flexible, as it may include a statement like "other types of studies were considered for inclusion if they were deemed to be highly relevant and of good quality."

Because of the significance of undertaking a quality knowledge synthesis, there are protocol registries that allow researchers to share their intent to publish on a topic prior to completion of the full review. Protocol registries should be used both to notify the research community of your intent to publish, and should be searched to ensure that no one else has already done so on your topic.

Some of the most prominent registries include:

- PROSPERO: a well-known registry for knowledge synthesis protocols on health-related topics

- JBI Protocols: a registry of published JBI protocols

- Open Science Framework Registries: a multidisciplinary registry for knowledge synthesis protocols

Retrieval

This section outlines the steps of a systematic search, which should be precisely followed when doing a review. If you are entering this stage of the review process, we strongly encourage you to reach out to a knowledge synthesis librarian at your institution (Alex Goudreau and Richelle Witherspoon provide this expertise at UNB) for assistance, and to familiarize yourself with the services that are offered. UNB Libraries offers 3 levels of review support, which are detailed on the Getting StartedGetting Started page. Depending on the level of service that fits the context of your research project, these steps may be facilitated (or even performed) by a librarian consultant or collaborator.

If you are going to be performing the search yourself, or with non-librarian team mates, the steps to search development and design are described here.

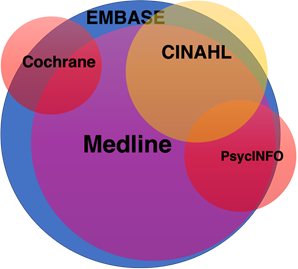

Knowledge syntheses generally require you to search between 4 and 6 different databases in order to comprehensively capture the unique content each holds. However, databases also overlap a lot within a discipline (see figure below for an example from the health sciences). A good search strategy seeks comprehensiveness even when there is also duplication.

There are a number of ways to determine which databases you should be searching for your review:

- Look for syntheses on topics similar to yours and see which databases they searched

- Check out the UNB Libraries Research Guide for your field and read the blurbs about the databases that are recommended there

- Talk to your supervisor to learn about the databases that are popular to / relevant in your field

- Consult with a librarian

Depending on the type of review you’re doing, you may want to limit the types of resources you include. For instance, some types of reviews only include peer-reviewed research, or randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or qualitative publications, or data. Other review types might explicitly exclude certain kinds of research, like grey literature. The decision of what types of resources you should include in your review depends on the question being asked and the type of review being done. For instance:

- Medical topics with RCTs available will tend to restrict only to RCTs or to RCTs and clinical trial reports

- Scoping reviews tend to be very inclusive of resource types, and will include things like trade journals, government and organizational reports, theses, and policy documents.

- Topics that deal with polarized topics and/or marginalized populations may benefit from a robust review of the grey literature.

Once you’ve identified the components of your question, it’s time to put them into words – as many words as you can think of. Synonyms are a really big part of systematic searching and there are a number of approaches you should take with each component of your question in your quest to identify all of them.

- Use a standard thesaurus, like the one on thesaurus.com

- Search in a database and check out the autofill options, then scan titles, abstracts, and subjects for new terms

- Check out the controlled vocabulary for the term (see an explanation of controlled vocabulary in the next section)

- Look to see if any there are any Process & Searchingthat cover parts of your topic and see what terminology they have used. If you use a substantive number of the search terms from any given review, you should give credit to that review in your methods section.

- Look to see if there are any existing hedges or filters (see below) for any of the components in your review.

Search Filters

Search filters, also called hedges, are pre-assembled search strings for specific topics. While search filters vary in quality and design, they offer an excellent basis for new searches and - in some cases - may replace one component of a search entirely. For instance, the Cochrane RCT search filter is excellent and can easily replace any other such narrowing option. When using a search filter (either in part or in whole) or when using a substantive portion of a search from another review, it is expected that the source be cited and the creator given credit.

For tips on how to find search filters, visit our Tips, Tools & Resources page.

Understanding Controlled Vocabulary

Controlled vocabulary is both a source of synonyms and another category in searching at the same time. Controlled vocabulary is a cross between the filing system of a database and hashtags (if hashtags were controlled and organized by cataloguing librarians).

In essence, most databases will have ‘subject terms’ for some components of your question that represents an entire concept as well as all the synonyms that are contained within that concept. Controlled vocabulary is a necessity for knowledge syntheses, and subject terms that are identified generally have to be searched both as subject terms and as synonyms.

To use controlled vocabulary, you go into a database and find the database’s thesaurus (also called its index, descriptors, subject terms, subject headings, or MeSH) and search within that thesaurus to find terms that represent your concept.

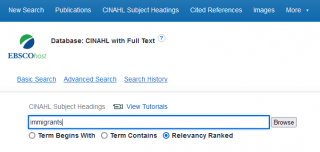

For example, a search in CINAHL for immigrants, came up with this:

- persons

- adult children

- emigrants and immigrants

- undocumented immigrants

- multiple birth offspring

- twins

- twins, dizygotic

- twins, monozygotic

- twins

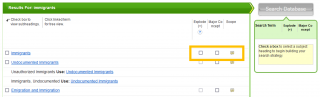

You can see here a branching structure that starts at a broad category and narrows down to more specific ones. In this case, we aren’t interested in ’persons’ in general, but particularly in emigrants and immigrants

You’ll notice, too, that under the broader category of emigrants and immigrants is the narrower topic of undocumented immigrants, which also fits with the population as it’s described in our question, so we want to include that subject term as well. This is done by ‘exploding’ the term, a process that’s covered in the next section.

Finding Controlled Vocabulary in an EBSCO Database

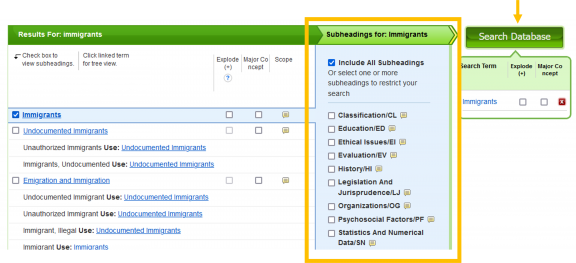

Each database has its own specific collection of controlled vocabulary terms and has slightly different approaches to how those terms can be found, selected, and added to the search. We provide one example of how it works (in EBSCO’s CINAHL database) here.

- From the CINAHL homepage, CINAHL subject headings are in the blue bar above the search box

- Use the search box to search CINAHL’s subject headings. If you don’t find a relevant subject term with your first search, try a few more synonyms, but be aware that there might just not be anything to find so don’t get too stuck on this step. Also, watch out for cases where there is more than one subject term for your topic – for example, there are lots of different kinds of physical activity and they will often each have separate subject terms.

- There are a few things I want to highlight on this page apart from the terms themselves and those are the three options to the right of the results box (below).

- Explode: Exploding a subject term allows you to include it and any other narrower terms that falls beneath it. Note that there will not always be an option to explode a term. Also note that some databases explode terms by default while others – like CINAHL - require that you select it manually. In most cases where the option to explode is available, you will want to use it. The exception is when the narrower terms are clearly not relevant to the search you want to perform.

- Major concept: Major concept limits use of subject terms to those classified as 'major' (there are also minor subjects). Systematic searches should not be limited to major concept as it is too restrictive.

- Scope note: Offers a brief explanation of how the database defines and implements that term in the database.

- When you select a subject term you want by clicking on the check box beside the term, it will produce this additional box that offers the option of narrowing further by subheading (which are different from subject headings). Don’t use these. Just ignore them entirely and go straight to adding your term to your search by clicking ‘search database.’

Truncation

Truncation allows you to type the root of a word into the database, put an asterisk at the end of it, and have the database search that root with all of its possible endings.

- In truncating truncation to truncat*, a search would pull back any results with truncate, truncated, truncates, truncating, and truncation.

- The trick to truncation is knowing how far to truncate a word. You have to make it short enough to include as many variations as possible, but keep it long enough that you don’t end up including variations you don’t want.

- E.g. Truncating it to truncati*, would still retrieve truncation and truncating, but not truncated, truncated or truncates. On the other hand, truncating it to just trun* would retrieve words like trundle and trunk, which aren’t relevant and will simply introduce noise into your search.

- Note: Not everything that can be truncated should be truncated. In cases where it isn't clear whether truncation is appropriate, consult with a librarian.

Phrase Searching

Phrase searching tells a database to search the words you’ve typed exactly as you’ve typed them. It’s most commonly used when you have a search term that includes two or more words and you want to tell the database to only bring back results that have all the words together and in the order you typed them.

- Searching government of Canada in a database will bring back any article that has government, of, and Canada. So you might get an article that uses the phrase ‘the government of Sweden sponsors three students to attend climate summit in Canada’, which is clearly not relevant.

- On the other hand, if you wrap the phrase "government of Canada" in quotation marks, you are guaranteed to pull back only articles that use that exact phrase.

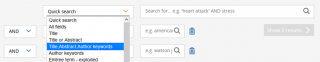

Search Fields

Search fields allow you to narrow down what part of an article you’re searching for your terms in. Search fields include article titles, authors, journal titles, abstracts, subject terms, ISBNs, and lots of other things.

It’s fairly common to limit a search to ‘title, abstract, and keyword’ or its equivalent in a database. Doing this will narrow down your search, and will usually do so without getting rid of relevant items.

Proximity terms allow you to search for articles that have two words close to one another but not necessarily side-by-side. It’s used to help create a relationship between two concepts in a search without forcing you to think up every possible way it could be phrased and type them out manually.

- E.g. curriculum N3 theories would search for curriculum within 3 words of theories and would bring back results that include such relevant phrases as theories of curriculum design or theories of curriculum reform

Note: Different databases have different commands for phrase searching (like N#, adj#, and w# - where # can be any number between 1 and 5). To find the command for an individual database, refer to that database’s help menu or to our Tips, Tools & Resources.

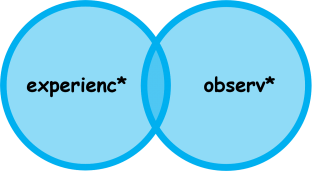

Boolean operators are commands that allow you to control how words are combined in a search, so that synonyms are searched differently than different components. Technically, there are three Boolean operators in databases (AND, OR, and NOT) but only the first two are used in knowledge synthesis.

Using OR

OR tells the database to bring back any item that uses any word connected by it.

- For example, connecting the words experience, perspective, and observation with OR would retrieve any item in the database that uses any or all of those words.

- In the context of a knowledge synthesis, OR is used combine synonyms and subject terms so that a search is as broad and inclusive as possible.

When performing a systematic search in a database, OR is incorporated by combining individual term searches in the search history.

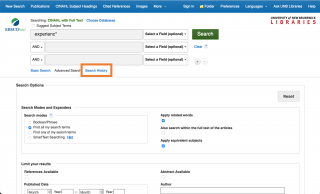

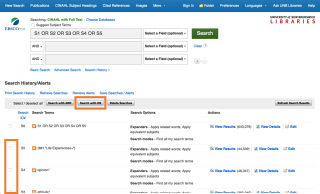

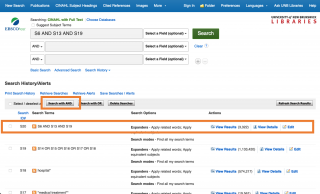

Using the EBSCO platform as an example, the first step to this is searching each synonym related to a single concept in your search in individual, serial searches. These individual searches are saved to the search history, which is linked to just below the database search boxes.

Once there, terms are combined by selecting each synonym and using the Search with OR button at the top of the search history. OR combinations must be cleared after each search.

Using AND

AND is used to combine different chunks of a question by telling the database to retrieve all results that contain every term connected by it.

- In this case, combining experience and immigrant with AND will bring back any item in the database that uses both words, but not those that only use one or the other.

Combining AND & OR

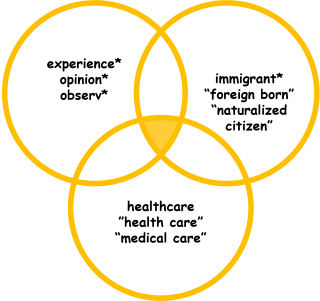

When AND is used in combination with OR, you’re able to create something like this, where the database retrieves every item that uses at least one term from each of the chunks in your question.

- For example, an item that’s retrieved in the combination below might use experience, naturalized citizen, and medical care or observation, immigrants, and healthcare.

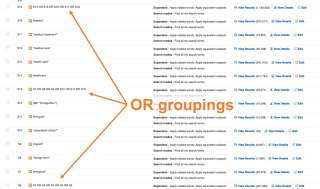

To use AND in a systematic search of a database, return to the search history in which the previous OR searches were completed and select each OR grouping. These OR groupings are then combined by using the Search with AND option at the top of the search history.

The final line of Boolean searching in a systematic search should look something like this:

Not Using NOT

NOT excludes any database result that contains a certain word. However, while it might be tempting to use, it can backfire in ways you might not expect or want.

- For example, if you’re doing research on healthcare in Canada and you’re not interested in other locations, you might be tempted to search Canada NOT “United States” or something like that. However, a lot of articles about Canadian healthcare are going to mention the US even if they aren’t about the US, and that’s where NOT tends to backfire. Lots of articles that are relevant to your search are going to use words to talk about peripheral topics, and using NOT can cause those to be unintentionally excluded.

- Because of this, you should consult with a librarian before implementing NOT in your search, as it is rarely (if ever) appropriate in knowledge synthesis. It’s better to be more specific in the search terms you include than it is to use NOT to exclude things. If using search terms for this purpose is not effective, screening out problematic articles during the screening phase may be the best answer.

Most databases offer options to limit search results after the search has been completed. These limiters are usually located on the left-hand side of the screen and allow the searcher to limit by things like publication year, type of resource, peer-review, geographic location, publisher, journal, gender, methodology, and language.

In general, only two of these options are acceptable for use in knowledge synthesis (publication year and language) and only in some circumstances.

Publication Year

Few reviews limit by publication year, and only do so because the research has changed so drastically over time that seminal research is no longer accurate or relevant. This tends to be the case in only two distinct situations:

- There has been a significant discovery in the field that has rendered original research obsolete.

- The topic is (or has been) socially polarized in such a way as to make early research severely biased and inappropriate / inapplicable in a current context.

Language

Language is commonly used as a limiter in searching, and is more-or-less neutral in terms of cost/benefit. On the one hand, language limits make sense when the researchers on the team only speak one or two languages and do not have funding to pay for translation of relevant articles. On the other hand, some non-English articles have an English abstract with them, but would be excluded from the search using the language filter. If there is a chance of such abstracts providing value to the research, then a language limiter would not be appropriate.

Note: When limiters are applied to a systematic search, these limits must be detailed and justified in the methods section of the manuscript. This being the case, limits are best used with conservatively and in consultation with a librarian.

Searching is an iterative process, which each successive search refining terms and commands until a final search design that balances comprehensiveness with sensitivity is decided on. With each successive test search, ask yourself:

- Am I getting relevant results?

- Am I missing things I should be getting?

- When I have irrelevant results, do they have something in common that I can use to get rid of them?

- Is one of the terms I used bringing in unwanted results?

- Am I getting too many or too few results?

- Are there terms in my results that I didn’t use, but that I should have?

Search development and design is a long and intensive process that often takes 30+ hours to do well. They also favour comprehensiveness over sensitivity. Final searches often have 4 – 8 thousand results per database, of which only 1-3% may end up being included in your final review.

Recording a Search

It’s always good practice to record your searches as soon as you run them, as this is both something that increases their replicability and something that is a necessary part of writing the final review. In most cases, the best and easiest way to record a search is to save the entire search history in PDF, Word, or Excel format.

Saving a Search

When you’ve settled on a final search, most databases give you the option of saving it. This means that you can walk away from the search, come back to it at a later date, and run it without having to re-type the whole thing, which can be useful in a number of ways. If you decide you want to save your search, you’ll need to create an account with the database you’re searching and then use the ‘save search’ or ‘create alert’ option in your search history to do it.

Exporting a Search

Exporting your search is the final step of the actual search, and it has two parts:

- Exporting your search history: best practice in knowledge synthesis is to append at least one search history to your actual paper, and some journals / publishers require you to submit all of them, so it’s best to get this right from the start.

- Exporting your search results: after you’ve exported your search history, you’ll need to export your search results into whatever tool you’re using. Depending on the database and on the size of your search, there are a number of different approaches to how you go about doing this, but generally speaking you just want to export all results as an RIS file that you will then import into your software.

Suggested Citation Management Software Options

When exporting your searches, you may choose to export them directly in a knowledge synthesis tool (like Covidence, Rayyan, or JBI Summari) if you are using one. Otherwise, citation management tools make the next steps of the retrieval process much easier.**

- Zotero

- Free resource, support available from UNB Libraries

- Can only import 3999 records at a time (won't tell you this until it times out)

- Mendeley

- Free resource, support available from one librarian at UNB Libraries

- Tutorials and other guides

- Can import at least 10,000 records at a time, quickly

- Endnote

- Subscription-based

- Tutorials and other info about using it for systematic reviews

** You may also choose to use a combination of both knowledge synthesis and citation management tools in your review. Many researchers use citation management tools for the de-duping and writing stages, and knowledge synthesis tools for the selection and appraisal stages.

Reporting a Search

When writing a knowledge synthesis, there are a number of details related to your search design and implementation that you will need to track and report (such as keywords, controlled vocabulary, databases searched, numbers of results, amounts of duplication across databases, and the date(s) the search was performed). For a detailed description of the search-related items you should be reporting, please refer to the PRISMA-S reporting guidelines.

Before going through the process of translating your search across databases and actually exporting your results, you should have your search peer-reviewed by someone – preferably a librarian trained in systematic searching.

A common approach to peer-reviewing searches is using PRESS (peer review of electronic search strategies) guidelines. The 2016 article that proposed PRESS has a list of questions / criteria for a reviewer to consider before approving a search. These questions include:

- Does the search strategy match the research question/PICO?

- Are there too many or too few search components?

- Does the search retrieve too many or too few records?

- Are there any errors in truncation, phrase searching and other operators?

- Are Boolean or proximity operators used correctly?

- Are subject headings used appropriately?

- Does the search include all spelling variants in free text (eg, UK vs. US spelling)?

- Does the search include all synonyms?

- Are acronyms or abbreviations used appropriately? Are the full terms also included?

- Have the appropriate fields been searched?

Translating a Search

In an ideal world, all your searches in all your databases would be identical and translation would be completely unnecessary, but in the real world we just have to do the best we can. Because different databases use different sets of controlled vocabulary, we have to translate our searches when searching across multiple databases. Translation is the act of adapting a search strategy for use in another database, including finding similar or equivalent subject terms in that database if they are available. During translation you may also have to make adjustments to the operators and search fields you use.

Managing Duplicate Results

Once you have all of your search results located and downloaded into Covidence or Zotero, it is necessary to go through those results and remove duplicate items. Sometimes called 'de-duping' this process is necessitated by the overlap between databases, which can result in some articles appearing in your search results 4 or 5 times. However, because each database also has its own unique content, some articles will only appear once.

De-duping is done differently by different people and when using different tools. Most tools have some form of duplicate detection and removal, but some tools perform the task better than others. In deciding how you want to do your de-duping you should consult with an expert or do some research to gain an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the tool you’re using.

The final retrieval process that invites new research into your review is the hand searching and cited by stage, which happens after an initial list of articles have been identified for inclusion in the review. These two processes offer one last chance for the review team to capture any literature that might have been missed at previous stages of the search:

- Hand searching reference lists: The act of reading through the reference lists of the articles you’ve selected for inclusion to find relevant research that might have been missed.

- Cited by searching: The act of searching through the articles that cite the articles you’ve selected for inclusion in your review. This can be done using the cited by feature in either Google Scholar or Scopus.

Grey Literature is “Information produced on all levels of government, academia, business and industry in electronic and print formats not controlled by commercial publishing, i.e. where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body.” (International Conference on Grey Literature)

Grey literature is often recommended in knowledge synthesis guidelines and standards because it helps to moderate the impact of publication bias, increases the currency of results, and increases inclusion of global literature. Evidence shows that the inclusion of grey literature reviews can and has changed whether interventions were deemed to be effective.

Some Sources of Grey Literature

- Databases: You will get at least some grey literature (like dissertations, trade journals, and reports) from the academic databases you’re already searching for your review, although grey lit will make up a relatively small percentage of your results and is generally not considered sufficient for grey literature searching.

- Dissertation Portals: Searching dissertation portals like the Proquest Dissertations & Theses database, library catalogues, institutional repositories, and government platforms.

- Search engines: Google can be used for grey literature searching as long as it is done thoughtfully and with appropriate use of advanced search tools. When using Google for grey lit searching, it is customary to restrict your review of results to those on the first 10 pages.

- Websites: You can search individual, relevant websites either through the website page itself or by using Google’s site searching feature.

- Conference proceedings: Conference proceedings reflect current research in the field and can be a good source for relevant research that received a negative result (and would therefore likely not be published in a journal). Conference proceedings can be found on conference host webpages, in some databases and repositories, through some journal websites, and by using conference hashtags.

- Clinical Trial Registries: Depending on your topic and question you may need to also look for clinical trials that are ongoing and those should mostly be in clinical trial registries. Major registries include clinicaltrials.gov, Cochrane CENTRAL, and WHO’s international Clinical Trials Registry search portal.

Tools to help with Grey Literature

- CADTH Grey Matters checklist

- University of Toronto template: How to find & document grey literature

- Critical appraisal of grey literature (AACODS checklist)

Selection

This is the stage where you apply the inclusion or exclusion criteria to your search results and is probably the biggest part of the knowledge synthesis process as it often means going through and reviewing thousands of results.

Before you start doing your article selection, we recommend working through the first 20-50 results with your co-authors and firming up what your inclusion/exclusion criteria are. You may find that you need to add - or be more specific about – one or more to make this phase successful.

When you do settle on your criteria, it’s absolutely vital that you stick to them like glue and that you communicate with your co-authors when you’re unclear about something. In a perfect world, you and your co-authors would go through all of your results independently and come up with the exact same inclusions because you’re applying the exact same rules to do it, so be mindful of this when you’re working through this process.

Note: in addition to criteria surrounding the topics covered within items selected for inclusion, you should have criteria relating to the types of resources you intend to include, as well as to your treatment of retracted articles and articles published in predatory or bad faith journals. For guidance on this topic, please review Predatory Journals and Article Retractions in Knowledge Synthesis.

For information about software that supports selection processes, visit the Tips, Tools & Resources page.

Synthesis

In the synthesis stage of the knowledge synthesis process, articles are read, assessed for quality, data is extracted, and an overview of all the existing evidence on a topic is done.

Critical appraisal (which is also known as ‘risk of bias assessment’) is the act of evaluating the quality of the articles and documents that you are going to include in your knowledge synthesis. It isn’t used in all knowledge syntheses but is considered best practice in most cases (exception: scoping reviews).

Critical Appraisal forms ask questions like:

- Did the article address a clearly focused issue?

- Were all of the participants who entered the trial properly accounted for at its conclusion?

- Were the groups similar at the start of the trial?

- Aside from the intervention, were the groups treated equally?

- Was the methodology appropriate?

- Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

For information about critical appraisal tools, visit the Tips, Tools & Resourcespage.

Knowledge syntheses incorporate critical appraisals into their manuscripts in different ways. A few examples include:

- Only including items that score above a certain threshold on all questions

- Only including items that score above a certain threshold on certain questions

- Describing the scoring of items in text and discussing the implications of research strength on the review conclusions

- Creating a table of critical appraisals for included articles and discussing the implications of research strength in the review conclusions

- Weighting research differently in the conclusions based on its critical appraisal score

- Including all research at equal strength regardless of score (not recommended)

Data extraction is the process of extracting and collating the relevant information from an article in one place for consideration and synthesis. This is typically done in table format with two to three researchers extracting data from each article and comparing their work in much the same way that article selection is done. The specific nature of the data extracted changes based on the type of review being done (and the type of data available in a given article), but often include things like:

- Population

- Size of sample

- Study design

- Type of data collected

- Type of analysis performed

- Data (quantitative or qualitative)

- Conclusions

For information about data extraction tools, visit the Tips, Tools & Resourcespage.

Write Up

The best way to learn how to write a knowledge synthesis is to read knowledge syntheses, like the ones we have linked to in our Public Zotero Group. There are also many books in the library collection that address all aspects of knowledge synthesis and make excellent resources to support the writing stage.

When it comes to knowing what to include in your report / article, however, the single best resource you can refer to is PRISMA, which produces a number of detailed reporting guidelines. In using PRISMA guidelines, you should refer at least to the PRISMA 2020 Checklist, the PRISMA-S guidelines for reporting a search, and the PRISMA flow chart that illustrates the searching and screening of articles.